Canberra International Music Festival

★★★★☆ A smart, challenging programme highlighting Shostakovich’s personal upheavals.

By Angus McPherson. April 30, 2017 – Limelight Magazine

In a revolution-themed festival, Shostakovich’s music was inevitably going to have an important place in the proceedings and in the second concert of the Canberra International Music Festival, titled The October Revolution: A Line in the Sand, the Russian composer was the main event. And yet, despite the concert’s title, this was a very personal, intimate Shostakovich on display, removed – as much as one ever could be in Soviet Russia – from the political turmoil of the time.

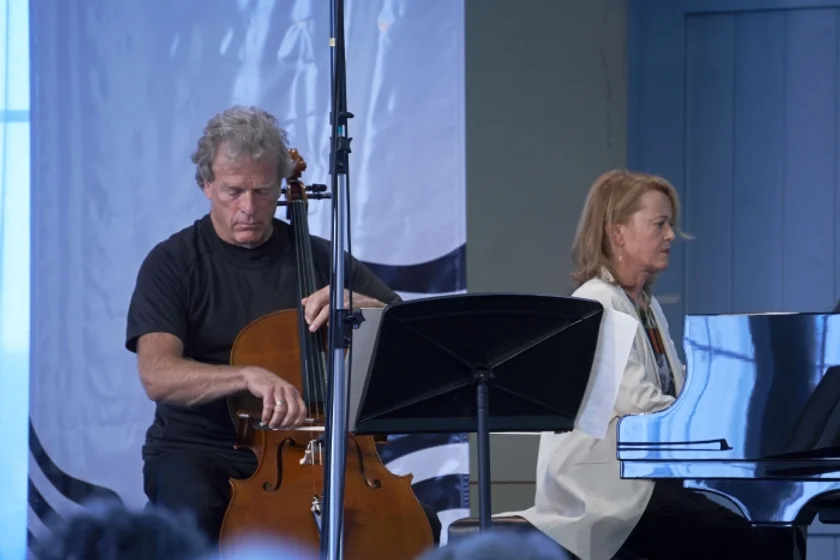

Cellist David Pereira and pianist Lisa Moore took the stage of the Fitters’ Workshop for Shostakovich’s 1934 Cello Sonata Op. 40. Written before the public denouncement of his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtensk, the Sonata speaks of upheavals in the composer’s love life. Shostakovich’s marriage to his wife Nina floundered when he became infatuated with a 20-year-old translator, Yelena Konstantinovskaya, and it was during this period that he wrote the Cello Sonata.

David Pereira and Pianist Lisa Moore performing Shostakovich Sonata CIMF April 29 2017, Fitters Workshop, Kingston. Photo: Peter Hislop

Pereira’s sound was penetrating and intense while Moore highlighted bright melodies in the upper register of the piano before plunging into its tenebrous depths. The first movement showed Shostakovich in a surprisingly romantic – almost sappy, for the often-sarcastic composer – vein, before it slid into darker, more ominous regions, Pereira drawing soulful melodies over Moore’s driving piano. The vibrant, folky second movement powered forward with hammering piano, tearing slides and bow slapping energy. Magically sliding harmonics against playful piano lines gave some relief from the energised momentum that, by the final note, had the audience struggling not applaud between the movements. The Largo entered more shadowy territory, Moore and Pereira delivering a deeply unsettling, visceral performance – Pereira’s burnished tone singing mournfully – before the fantastically quirky, toe-tapping finale. While the Sonata might be the result of personal turmoil, the political was never far away. Not long after the affair ended and Shostakovich and Nina reunited, Konstantinovskaya was anonymously denounced and arrested. Pereira’s smooth cello lines opened the finale of the concert, taken from the other end of the Shostakovich’s life. Shostakovich’s 1967 Seven Romances on Poems by Alexander Blok, Op. 127, was written in the aftermath of a heart attack that left him unable to compose for a period. The cellist Rostropovich had asked Shostakovich for something he could perform with his wife, soprano Galina Vishnevskaya, and the composer soon set Song of Ophelia followed by six more settings of Blok’s Symbolist poems, writing piano parts (for himself) and a violin part for David Oistrakh.

Soprano Louise Page brought a quiet delicacy to Song of Ophelia, her sound ringing with vibrato, before she opened up in the apocalyptic Gamayun, the Bird of Prophecy, Roland Peelman leaning into the weighty piano part. Page brought a warmer sound to We Were Together (That Troubled Night) while James Wannan’s violin trickled anxious running figures. Pereira’s double-stopping created an eerie, sliding texture in The City Sleeps while The Storm saw more thunder before the still aftermath of Secret Signs. If Page’s storm and apocalypse felt a little too restrained, this did allow her bring greater drama to the heart-rending climax of the final song, Music, before its clouds gave way to a tranquil, if not entirely unqualified, sense of peace. The two other works on the programme helped balance the emotional weight of the Shostakoviches. The concert opened with Mozart’s “Kegelstatt” Trio in E Flat Major for clarinet, viola and piano, cheerfully delivered by Orit Orbach, Florian Peelman and Lisa Moore respectively. Nicknamed “Skittles” (though this seems to have been a moniker chosen by a publisher rather than the composer) the bright trio was somewhat at odds with the rest of the programme – it almost fits the theme in that it was composed a couple of years before the French Revolution – but it did provide a light contrast to the more intense works.

David Pereira joins Elena Kats-Chernin and Tamara-Anna Cislowska. Performing Russian Roots and Rags. CIMF May 6 2017, Fitters Workshop, Kingston. Photo: Peter Hislop

Peelman opened the second half of the concert with the world premiere of Belgian composer Frank Nuyts’ 20th Piano Sonata, named (by the composer) “Radical Risk” or “La Cucaracha”, for the Spanish folk song about a limping cockroach that experienced a revival – with new lyrics – during the revolutionary upheavals in Mexico in during the first decades of the 20th century. The work opened with a Bluesy jazz riff, a hesitant, off-kilter rhythm that would recur throughout the first movement of the piece, jolting and disrupting the structure and moods of the piece – it high-jacked what seemed to promise a more tranquil atmospheric section and disrupted a foray into Minimalism. Peelman tackled the halting rhythms and varying metres with an intellectual focus and precision, deftly managing shifts into fragments of Debussy-esque colour and the brooding, winding melodies of the second movement. Driving rhythms and jazzy energy returned in the finale, the long-awaited quotation from La Cucaracha getting a laugh from the audience, before the opening’s limping riff brought the piece to a close. In many ways this was – aside from the Mozart – a more challenging programme, but it paid off. And judging by the murmurings from the audience, Pereira and Moore’s stunning performance of Shostakovich’s Cello Sonata has won the composer a few more fans.

Source: Angus McPherson (2017, April 30) Limelight Magazine

by

by